When someone mentions Grand Seiko, you probably think of the Snowflake, or Tudor, the Black Bay, or Nomos, the Tangente, but when someone mentions IWC, depending on your personal watch collecting preferences, one of two watches might pop up: the Big Pilot’s Watch or this one, the Portuguese Automatic. While the Portuguese Automatic is such an old and popular watch it has been reviewed countless times already, in 2015, it was subtly reinvented. While it’s virtually identical from the point of aesthetics (thankfully), its respected in-house Cal. 50000 was replaced with the more advanced Cal. 52000. That provided the perfect excuse for me to review one of my all-time favorite watches, so join me as we critically analyze this legend.

The Portuguese has always been an interesting watch to me from virtually every angle, including the history, aesthetics and even the size. Visually, the Portuguese, and specifically this Automatic, has a distinctly Germanic look, not unlike you would find from the most prolific greats, like Nomos, Glashutte Original or A. Lange & Sohne.

It has that character, I suspect, thanks to its combination of a silver-plated dial, which appears white, and its ultra-clean minimalist appearance. While IWC is a Swiss company, it is located in the German-speaking region of Schaffhausen, which if you’ll find it on a map, appears to be more surrounded by German land than it does Swiss. It may be here that the Portuguese, either its oldest ancestors or this latest iteration, inherited this German aesthetic.

The original Portuguese had a simple seconds subdial at 6:00 and little else, but the modern Portuguese Automatic has not only small seconds, at 9:00, and a date at 6:00, but quite an amazing power reserve at 3:00. Despite having two subdials and a date window, it remains completely uncluttered and extremely legible. If it weren’t so pretty, you might even call it a tool watch.

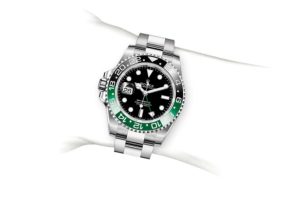

Being such a popular watch, there’s no surprise that it’s available not only in many different flavors (by which I mean dial colors and metals) but also models as well, like the Hand-Wound 8 Days, but this silver dial and blued accent version is definitely my favorite, followed somewhat closely by the same dial with gold accents.

The 42.3mm case may seem classic, but not altogether interesting, and there you’d be wrong. It is both behind its time and ahead of its time. When the Portuguese came out, it was absolutely massive for the desirable proportions of the day, reminiscent of a pocket watch strapped to the wrist (because it basically was), but as many other watches have had to grow into the preferred sizes of the post-2000 world, the Portuguese was able to remain very comfortable at sizes its long been produced at.

Like its diameter, its 14.2mm thickness is right in line with other watches of today, but I’m inclined to give the Portuguese Automatic more leeway when you see just how massive the movement inside it is. Interestingly, my own measurements show it to be 0.3mm thinner than IWC lists it at. Thankfully, the crown doesn’t screw down and, with just 30 meters of watch resistance, this is not recommended as a substitute for an Aquatimer dive watch. As an aside, this watch has a very interesting winding feel. It’s quite smooth, but the clicks are very far apart, as opposed to the high frequency of a GS spring drive or a the almost total lack of audible clicks in an Omega 8500. As you may expect, it can take a little while to hand wind this watch from 0 hours to 7 days, although thanks to its great Pellaton automatic winding system, you’ll probably never need to do that.

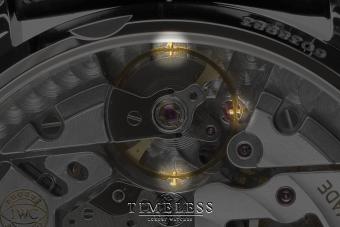

One of the remarkable things about IWC as a company is that their in-house movements are very often fitted to cases, or vice versa as the order of creation dictates. Sure, 42.3mm is quite large for a dress watch, but you really must hand it to IWC, they’re using every last millimeter for this astonishing movement, the Cal. 52000, the successor to the Cal. 50000. It’s been awhile since I’ve had the privilege of breaking down a movement for you, so let’s take a moment and look at this horological work of art.

While I’ve noted, as I will undoubtedly again when it comes to their pilot watches, touches of German design, the movement seems to be very much in the Swiss style. You’ll find no 3/4 plate here, replaced instead by the heavily skeletonized top plate, hiding almost none of the workings within. This is one reason why IWC’s in-house movements are so fascinating to look at.

Here we can see that IWC has gone with a traditional high-end Swiss watchmaking approach. While the fact that it uses a variable inertia free sprung balance is unchanged from its Cal. 50000 predecessor, the rate is, which has now increased to a more ordinary 28,800 BPH. IWC is a very interesting company because it’s one of only a tiny few that produces several current-generation movements with either free sprung or regulated balances.

Looking close to the balance wheel allows me to highlight the screws in the rim for you. These are used for both adjusting the poise and rate of the balance wheel, which allows it to do away with a need for a regulator. While ultimately more stable, it’s also more difficult to adjust, and variable inertia balances are almost always associated with upper-price range watches like Patek, JLC, Rolex and Omega, although there are recent exceptions from Damasko and Tudor, for instance. This particular iteration is one of the oldest and most traditional of the designs, with screws on the outer rim of the balance. Rolex, by comparison, uses a similar approach, but on the inside of the balance. JLC often uses the same approach as IWC does here, as does Tudor in its new movements.

Getting really close now allows us to view an even rarer design, the Breguet overcoil. Today this design is seldom employed outside of Rolex and Breguet, where it’s used to increase the stability of the movement.

One of the most important changes from the Cal. 50000 is the use of twin mainsprings to reach its amazing 7 day power reserve. This was probably a decision made to increase stability and multiple-mainspring designs are becoming much more common today.

Another major change is that the bidirectional automatic winding mechanism has now been made from ceramics. Automatic winding systems are subject to a lot of friction and wear, so the choice to make them out of ultra-hard ceramics makes perfect sense.

Although it’s now made from ceramic, the fundamentals of IWC’s highly unusual and efficient Pellaton automatic winding mechanism have not changed in the Cal. 52000. At its heart is a pawl system and one of the only similar designs to this is found in Seiko’s magic lever equivalent, although there are important differences in both. Its operation is devilishly simple. The rotor is attached to a cam which, when rotating, pushes those pawls (the little ceramic hooks) one way or the other. In one direction, let’s say clockwise, the rotor rotates and one pawl will lock into the wheel and move it while the other will slide harmlessly over the teeth. When the rotor spins counterclockwise, the opposite happens. The beauty, of course, is that this elegant mechanism allows very simple and reliable bidirectional winding.

Here is the beautiful rotor that it’s connected to, thankfully skeletonized so we can see more of the movement underneath. The gold emblem is a nice touch, and the entire rotor can be upgraded to gold if you skip the basic Portuguese Automatic and go for something more elaborate like the Portuguese Perpetual Calendar.

So that’s the IWC Portuguese Automatic, one of my all-time favorite watches. It didn’t really need a movement update as even the “old” 50000 was still one of the best available, but I’m glad it got it nonetheless. The Cal. 52000 keeps the original’s best traits and increases the beat rate while hopefully reducing isochronism and wear in the automatic winding system.

The IWC Portuguese Automatic is a classic because it’s compelling on every level. There are plenty of beautiful watches, and even quite a number of watches with great movements, and yet other watches with fascinating histories, but it’s a relatively rare thing to bring all three together into a single model. For those reasons, the Portuguese Automatic is, without any doubt, my single favorite IWC, one of my favorite watches we carry and one of my favorite watches of all time.